1.

Compassion is penetration: yourself in the other, the other in you. Thrusting and ingesting are two processes known to cause fatigue.

2.

How do we experience compassion fatigue?

Is it a thrusting fatigue? Something like the productive throbbing in your limbs after the gym? An n += 1 fatigue, where you expend yourself in order to improve yourself?

Or is it an ingesting fatigue? Something like a hangover? An n -= 1 fatigue where you gain nothing except a return to a slightly compromised baseline?

For me, it’s the latter.

3.

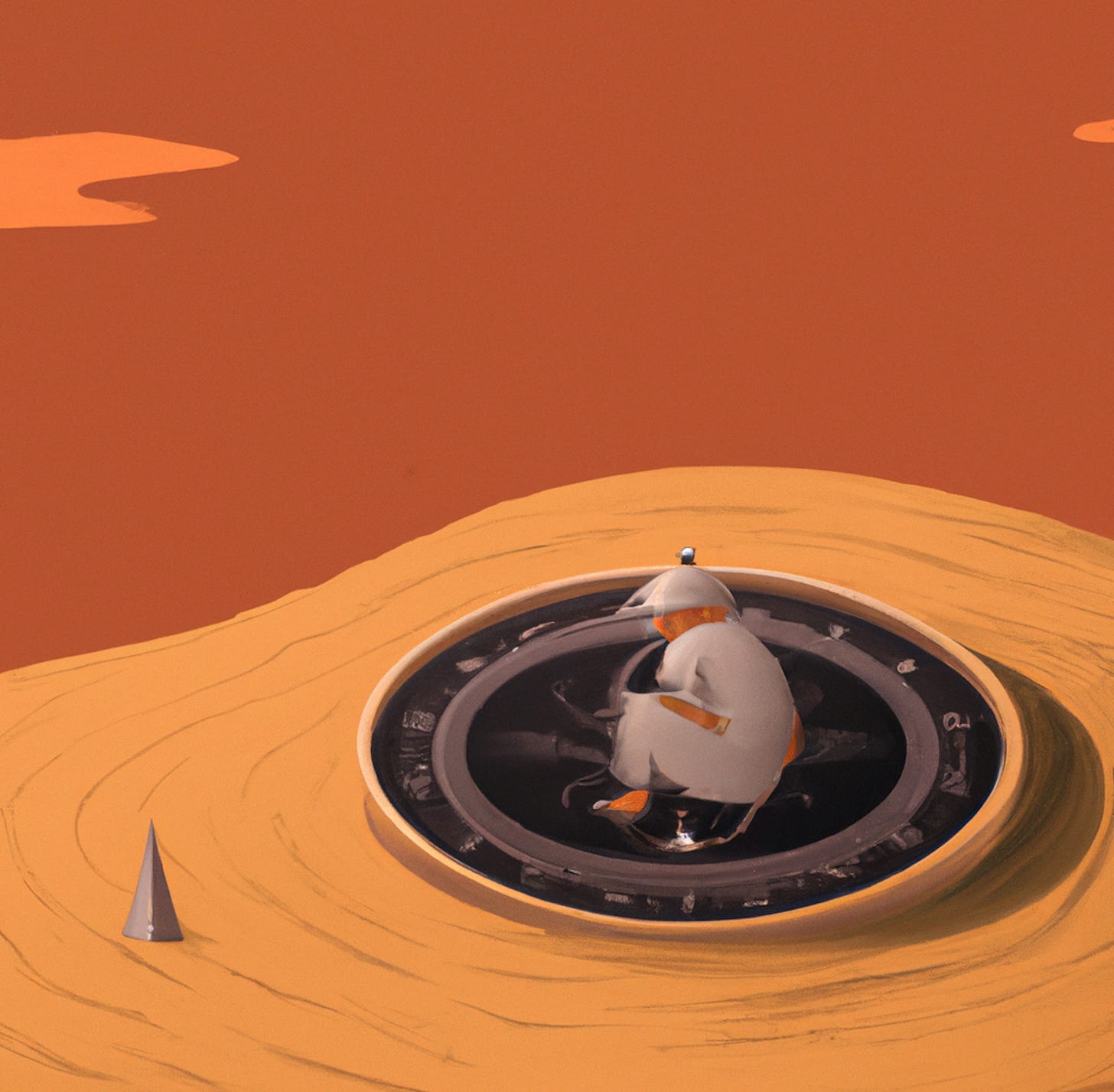

The presence of “compass” in “compassion” is no coincidence—it’s a warning. With every empathetic utterance, you respawn outside yourself. At first, it’s no big deal; you flicker out of phase with your body like two stacked circles briefly becoming Venn diagrammatic. You see yourself from a foot away, and by issuing a single step, you become whole again. When your compassion is chronically solicited, each respawn throws you farther from your body. You offer ‘I’m sorry for your loss’ and, poof!—you’re shirtless in your neighbor’s yard. After one too many ‘I’m sorry to hear that’s, you’re catapulted deep into the boonies of bumfuck nowhere. You come to buck naked, head pounding, needing a compass to determine ass from elbow. Meanwhile, your body—the semi-intelligent humanoid husk others mistake as you—is out there, ravaged by reflex, going through the motions as you stumble through deep sands, swatting locusts.

This is normal. It’s always been this way; you just never noticed. Compassion has always been extravagantly expensive and viciously unmooring. Back in the day, before screens, networking, and smartphones, I was ignorant of its cost. My social circle was lean—mom, dad, brother, a dozen or so non-nuclear relatives, the odd friend, and a handful of acquaintances—and struggle within my clan was infrequent. This was a manageable arrangement. On the rare occasions I was called to empathize, I never respawned too far from myself, my back-to-body odysseys were uneventful, and I was allowed to rest—to heal between spawnings.

Nowadays, in my line of work1, there are too many faces of flesh and pixel—too many urgent raps at the door for spare butter and change—too many voices boring their woes into my skull. Crisis work exponentially increased the number of those vying for my attention and compassion.

The demand has increased, yet I remain a simple primate. I’m ceaselessly respawning, given no time to recharge, condemned to confused sojourns in odd wildernesses—whiplashed as I pray for the North Star.

Back in the real world, I’m still on the clock—I’ve got a job to do! Unbeknownst to the callers, they’re speaking with my humanoid husk, who’s busy constructing the illusion of empathy. It intones, ‘I’m sorry to hear that. I’m sorry to hear that. I’m sorry to hear that,’ in a seedy—albeit valiant—effort to save our shared face. This is the deal I’ve made with my husk. When I’m off in the boonies, it offers the requisite empty spun-sugar pleasantries while I focus on navigating the strange terrains—finding my way back so we can stop pussyfooting around and dole out the real McCoy.

Like amputated limb and maimed body, I share a phantom kinship with my husk. Through this tether, I can hear each caller’s hysterics echo across the landscape, but I’m unable to respond. This distance breeds a sour guilt—I’m guilty, perhaps even deficient, because I’m not really there. They may hear my husk say, ‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ but it’s not me; it’s an occupational obligation.

When I think this way, part of my psyche fights back, urging me to cut myself some slack. As a garden-variety human whose job happens to be speaking with 1,600 people each year, I've come to find solace in ideas like Dunbar’s number. Dunbar’s number suggests the architecture of the human brain places a hardwired limit on the number of meaningful social relations we can maintain. This maximum number is said to be 150.

It’s freeing to think that I’m not psychophysically wired to speak to 1,600 people a year, let alone sincerely care about them—trying to do so would be a surefire way to resign myself to galloping neurosis. It’s comforting to know I can't be blamed if I come off as calloused or aloof. My aloofness is simply a protective reflex—no different than the one that pulls my hand away from a hot stove. My callousness is not because I don’t care; it’s because I cannot care—it’s my body saying: “I’m sorry, but I’ve decided not to pursue a meaningful relationship with you; you’re not one of my 150. Please, don’t take it personally!”

Despite this knowledge, I grow increasingly numb. I fear I'm in danger of becoming a permanent resident in the boonies between self and husk. Unlike regular nine-to-fives, my closing bell rings hollow. When the clock strikes five, I don’t rush into my husk like a child called for dinner. The numbness respects no bounds. It bleeds into my life, infecting my relationships with an ambient blah-ness.

I don’t know if I can find my way home again. My compass doesn’t work, and I've never learned to read the stars. I've been holding out for something unexpected—something with enough magnetism to reunify me. But even the sudden death of my grandmother, my Nanny, the most joyful spirit in my life, was not a strong enough clarion call to bring me back. I desperately wished to return, to grieve with everyone. But I no longer walk among them; my husk appeared in my steed, making good on its deal to save our face. It didn’t quite know what to do. It didn’t cry or brood; it appeared stoic and calm, which others mistook for fortitude. I can tell this worries my mother. I heard her ask my husk if I ever cried over Nanny’s death. My husk answered, “Yes,” but this is a lie, and it terrifies me.

4.

If there is a God who says, "love thy neighbor as thyself," why didn't he give me a body immune to compassion? Why does it buckle under its weight? If this is His word, why must it deplete?

Some contend if everyone were able to experience the suffering of others as their own, humanity might be a little less fucked. I'd agree…if we still lived in small villages and the internet didn't exist.

When social life is a handful of village folk or a small brood, "love thy neighbor" is a beautiful sentiment. In our modern world, where we are bombarded with the faces of infinite neighbors, it could prove disastrous.

Nowadays, I imagine we come into contact with more people, digitally and physically, in a single month than our ancient counterparts would see in a lifetime. According to Dunbar's number, we’re incapable of imbibing the glut of faces fed to us by social media, city life, work, family, dating apps, advertisements, TV shows, movies, etc.—despite our good intentions, we’re simply not designed to love all of our neighbors.

If we tried to love all of our neighbors, to empathize with every face—we'd all become husks, walking around empty, insincere, and neurotic, placing coins into outstretched hands reflexively, not because we care. Saying ‘I’m sorry to hear that’ to vulnerable strangers because it’s socially expected, not because we care.

Humanity would look better on the surface, but we'd still be fucked.

I believe humans to be compassionate by nature, but it is not someone’s nature or attitude or socioeconomic background that dooms them to a life without wings—it is their body.

5.

So what now?

Don’t let your good deeds catch up with you. There is a psychophysical threshold where they cling to you, bringing not karmic gains but gross fatigue. We should aim to express as much sincere empathy as possible to as many people as possible, prioritizing those who really need it while at the same time making sure to recharge so we never get perpetually lost in the boonies.

Check thyself before thou wreck thyself.

For the past two years, I’ve worked full-time in a crisis call center.

I’m in a lot of digital circles with a lot of emotional outpouring, my husk is frequently on call, but I’m close enough to find my way back easily. For whatever reason, I’ve tucked you (your avatar at least) into my 150, so I’m genuinely right here when I say, this sounds like a fucking nightmare and please take care of yourself. The analysis of thrusting vs ingesting is brilliant. Compass as well. You nailed this, Will.

Wonderful reflection here... lots of wise words and questions we all have rendered so well! I completely agree that we should show empathy but never to the extent that it harms us to do it! Compassion extends to oneself too!